italiano a seguire

A green place to rest...

Between the level turf and the herbs let there be a higher piece of turf made in the fashion of a seat, suitable for flowers and amenities; the grass in the sun’s path should be planted with trees or vines, whose branches will protect the turf with shade and cast a pleasant refreshing shadow.

'Orto Mediovale' Perugia Agricolture University

—Book VIII, Chapter I: “On small gardens of herbs.” Piero de’ Crescenzi, Liber ruralium commodorum (1305-09). (See Catena, the Bard Graduate Center’s Digital Archive of Historic Gardens and Landscapes for more information.)

Above: Honor Making a Chaplet of Roses, ca. 1425–1450. South

Netherlandish. Wool warp, wool wefts; 93 x 108 in. (236.2 x 274.3 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1959

(59.85).

Turf benches were among the most distinctive features of medieval

gardens, and are depicted in many paintings and tapestries.

Such benches

may be rectangular, circular, L-shaped, or U-shaped; the U-shaped type

is known as an exedra.

Regardless of their shape, the benches were

usually constructed with low-walled frames made out of brick, wood,

stone, or wattle (woven willow). The frames were then filled with soil

and the surfaces were topped with turf. Turf seats were placed in the

middle of the garden or against one of its walls, and were sometimes

incorporated into the enclosure. Arbors or trellises were sometimes

built into the seat to provide shade and shelter, while circular benches

were constructed around single trees.

Not all turf benches were constructed within a frame; some had grass

growing on all sides, as seen in the tapestry shown above. The same

plants and flowers that grow in the lawn are shown growing in the turf

of the bench. It’s important to note that although the grass growing on

this turf bench looks perfectly even on all sides, it would actually be

very difficult to achieve such uniformity, since not all sides would

have equal exposure to the sun. It is hard to match the perfection of a

painted image when working in three dimensions in a re-created medieval

garden.

|

| 'Orto Mediovale' Perugia Agricolture University |

The simplest form of turf bench, and the easiest one to replicate, is

the four-walled rectangular frame with turf growing only on the top of

the bench. Such benches are very common in representations of medieval

gardens, as in the view through the window in The Annunciation:

Above: Workshop of Rogier van der Weyden (possibly Hans Memling, active by 1465, died 1494) (Netherlandish, 1399/1400–1464). The Annunciation

(detail), 1465–75. Oil on wood; 73 1/4 x 45 1/4 in. (186.1 x 114.9 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan,

1917 (17.190.7).

This example is especially interesting because the benches that

border the paths serve not just as seating, but also enclose the

interior of the garden. Many of the same plants growing on the little

flowering lawn in the foreground also grow amid the grass of the bench.

The bench near the back wall of the garden is used to display the potted

topiaries tended by the woman gardener.

Turf benches are often included in re-created medieval gardens, such as Queen Eleanor’s Garden at Winchester Castle, designed by Dr. Sylvia Landsberg. The garden was named after Eleanor of Provence

and her daughter-in-law, Eleanor of Castile. Such a garden would have

been used as a private retreat; the turf bench has been fitted into an

intimate space that invites conversation and relaxation. The trellis

surrounding the turf exedra is covered with red and white roses.

The turf bench is such a distinctive feature of the medieval garden

that we would like to construct one here at The Cloisters. There is only

one site that seems suitable, and that is at the back of Trie garden.

This garden is planted as a single field of herbs and flowers, and is

meant to evoke the millefleurs tapestries in the collection (e.g., the Unicorn in Captivity,

and The Lady Honor tapestry itself). A bench framed out of cedar boards

faced with wattle and planted with turf and small wildflowers would

complement the design of the garden and allow visitors to see an

important medieval garden feature.

We are renovating Trie garden this spring, and a space for a turf

bench will be included in the new design. I’ll keep you updated as we

develop our plans. In the meantime, consult Dr. Landsberg’s book, Medieval Gardens, and try constructing your own medieval turf bench!

—Corey Eilhardt

Sources:

Harvey, John. Medieval Gardens. Beaverton, Oregon: Timber Press, 1981.

———”Sweet Repose.” Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 120.10 (1995): 626–628. Print.

Landsberg, Sylvia. Medieval Gardens. London: Thames & Hudson, 1996.

Paul, Martine. “Turf Seats in French Gardens of the Middle Ages (12th–16th centuries).” Journal of Garden History. 5.1 (1985): 3–14. Print.

The sight is in no way so pleasantly refreshed as by fine and close grass kept short. It is impossible to produce this except with rich and firm soil; so it behoves the man who would prepare the site . . . first to clear it well from the roots of weeds, which can scarcely be done unless the roots are first dug out and the site levelled, and the whole well-flooded with boiling water, so that the fragments of roots and seeds remaining . . . may not by any means sprout forth. Then the whole plot is to be covered with rich turf of flourishing grass, the turves beaten down with broad wooden mallets and the plants of grass trodden into the ground . . . . For then little by little they may spring forth closely and cover the surface like a green cloth.

The sight is in no way so pleasantly refreshed as by fine and close grass kept short. It is impossible to produce this except with rich and firm soil; so it behoves the man who would prepare the site . . . first to clear it well from the roots of weeds, which can scarcely be done unless the roots are first dug out and the site levelled, and the whole well-flooded with boiling water, so that the fragments of roots and seeds remaining . . . may not by any means sprout forth. Then the whole plot is to be covered with rich turf of flourishing grass, the turves beaten down with broad wooden mallets and the plants of grass trodden into the ground . . . . For then little by little they may spring forth closely and cover the surface like a green cloth.

—Albertus Magnus, De Vegetalibus, translated by John Harvey in Medieval Gardens, 1981.

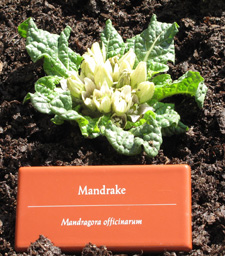

The Mandrakes Bloom Again…

The mandrake, credited with both medicinal and magical powers over the course of many centuries, has accumulated more lore than any other plant in the Western tradition. Above: One of a colony of five spring-blooming mandrakes in Bonnefont garden. In March, this famous member of the nightshade family produces tight clusters of short-stemmed bell-shaped flowers.

Mandrake (mandragora) is hot and a little bit watery. It grew from the same earth which formed Adam, and resembles the human a bit. Because of its similarity to the human, the influence of the devil appears in it and stays with it, more than with other plants. Thus a person’s good or bad desires are accomplished by means of it, just as happened formerly with idols he made. When mandrake is dug from the earth, it should be placed in a spring immediately, for a day and a night, so that every evil and contrary humor is expelled from it, and it has no more power for magic or phantasms.—Hildegard of Bingen, Physica (translated by Patricia Throop)

___________________________________________

In the later Middle Ages, the leaves, stems, and flowers of this aromatic member of the mint family were used to effect cures for many ills, and provide protection from both spiritual and bodily harm. Photograph by Nathan Heavers

Rosmarinus

Libanotis which the Romans call Rosmarinus & they which plait crowns use it: the shoots are slender, about which are leaves, small, thick, and somewhat long, thin, on the inside white, but on the outside green, of a strong scent. It hath a warming facultie . . .—Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, Book III: 89It is an holy tree and with folk that hath been rightful and just gladly it groweth and thriveth. In growing it passeth not commonly in height the height of our Lord Jesu Christ while he walked as a man on earth, that is man’s height and half, as man is now; nor, after it is 33 years old, it growth not in height but waxeth in breadth and that but little. It never seareth all but if some of the aforesaid four weathers make it.—Friar Henry Daniel, “little book of the virtues of rosemary,” ca. 1440

Above, from left to right: English daisies introduced into the garth garden in Cuxa Cloister some years ago; a realistic representation of the garth of a Carthusian monastery by Gerard David; the English daisy, Bellis perennis.

The sight is in no way so pleasantly refreshed as by fine and close grass kept short. It is impossible to produce this except with rich and firm soil; so it behoves the man who would prepare the site . . . first to clear it well from the roots of weeds, which can scarcely be done unless the roots are first dug out and the site levelled, and the whole well-flooded with boiling water, so that the fragments of roots and seeds remaining . . . may not by any means sprout forth. Then the whole plot is to be covered with rich turf of flourishing grass, the turves beaten down with broad wooden mallets and the plants of grass trodden into the ground . . . . For then little by little they may spring forth closely and cover the surface like a green cloth.—Albertus Magnus, De Vegetalibus, translated by John Harvey in Medieval Gardens, 1981.

This famous passage, which was to be repeated verbatim in the following century by Pietro Crescenzi, is an eloquent testimony to the importance of turf in the medieval garden. A grassy enclosure or lawn was a feature of both monastic and secular gardens. In the article “The Medieval Monastic Garden” (Medieval Gardens,

ed. Elisabeth MacDougall, 1986), Paul Meyvaert cites the

twelfth-century cleric Hugh of Fouilloy, who considered that the green

lawn of the cloister not only refreshes the eyes, but also brings the

eternal paradise before the minds of beholders.

John Harvey considers a drawing of a game of bowls,

dating to the reign of Edward I, to be the earliest representation of a

large and truly leveled lawn, comparable to the lawn at the Palace of

Westminster laid down in approximately 1239. The site was leveled with a

roller, and turf was later laid down and mowed. Sylvia Landsberg notes

that turves could be purchased by the thousands, and that in July of

1272, Eleanor of Castile paid one of her squires to perform nightly watering of two cartloads of turves, newly laid in a pleasure garden in June (Medieval Gardens, 2003).

While a pure and velvety sward

might have been the ideal in some situations, medieval lawns may more

often have been of the flowering type—a type that was certainly

deliberately created in some if not all contexts. The flowering mead or

meadow was an important element of the pleasure park. The locus amoenus,

or “pleasant place,” of antiquity and the Middle Ages, in which many

poems and romances were set, included both flowering meadows and groves,

and both are included in medieval representations of Paradise.

Even when and where great pains were taken to exclude them,

dandelions, plaintains, and daisies would have sprung up, as they do

now. Whatever the gardener may have felt about them, they are lovingly

and minutely depicted in many paintings and tapestries.

—Deirdre Larkin

______________________________________________________

Il giardino, universo complesso, fin dall’antichità è stato concepito come corpus dalle profonde simbologie.

Nella stratigrafica allegoria del giardino, infatti, dove si declina la grammatica dei quattro elementi fondamentali terra, acqua, aria e fuoco, sono rintracciabili più livelli interpretativi dai variegati assemblaggi: quello della simbologia delle piante che vi sono coltivate, quello della composizione geometrica e della forma e infine quello degli apparati decorativi.

Se i complessi legami tra piante e astrologia avevano dato origine a quella sorta di alchimia verde, dove sull’incerto confine tra magia e scienza, le indicazioni terapeutiche s’intrecciavano con quelle propriamente magiche, retaggio di una sapienza ancora più antica, è con Nicholas Culpeper, erborista vissuto nella prima metà del ’600, ma anche grande astrologo, che scienza delle piante e astrologia si uniscono in un grandioso connubio.

Negli studi di Culpeper, che recupera antichi saperi, dalle caratteristiche dei pianeti e delle costellazioni si derivava, in base alle loro corrispondenze astrali, le proprietà officinali delle singole piante, conoscenza questa che ben presto si perse tra le maglie dello scientismo del nuovo secolo.

Ma anche la stessa forma del giardino, declinata secondo i moduli di una geometria sacra, secondo il rispecchiarsi del cielo, definisce uno spazio dalle segrete risonanze.

Ne sono conferma i giardini monastici, dove si coltivava la sapienza delle erbe, racchiusi in un quadrato simbolico e protetti da alte mura, a significare la segretezza della pratica ma anche una magica difesa. In sostanza una sorta di microcosmo semantico dove le piante erano probabilmente collocate in relazione alle loro ascendenze astrologiche per derivarne maggiore vigore e catturarne così i benefici influssi astrali.

Nel Rinascimento poi, con la riscoperta della Divina Proporzione e la serie armonica del Fibonacci, i disegni dei giardini s’informano secondo quelle geometrie significanti, che improntano la segreta armonia dell’universo dal regno animale e vegetale fino a quello minerale.

La stessa dialettica dei quattro elementi, che sta alla base delle metamorfosi della natura e che affiora in frammenti decorativi nello scenario di parchi e giardini, dà vita ad una intrigante e scenografica messa in scena in un crescendo simbolico ispirato al filone esoterico.

D’altra parte, come in uno specchio, il giardino tout court, è stato utilizzato anche come metafora nel linguaggio alchemico, a convalidare, ancora una volta, questo stretto legame tra studio della natura ed elevazione spirituale. In sostanza una sorta di “agricoltura celeste” che diviene allegoria della pratica alchemica.

I significanti apparati decorativi poi segnano, in una vertigine di simboli, i punti salienti di un cammino sapienzale, che si snoda attraverso il giardino, come in una sorta di labirinto iniziatico e che rimanda analogicamente ai cosiddetti “viaggi” o “prove” delle antiche iniziazioni, tramandatesi nel tempo attraverso i rituali delle consorterie iniziatiche.

Il giardino così macchina complessa emerge in un gioco di segreti intrecci e antiche assonanze distendendosi in accenti di bellezza e di poesia.

Nel nostro mondo attuale dove la funzione estetica e visiva ha preso il posto di altri valori, si rende necessario recuperare l’universo simbolico del giardino, che significa poi recuperare saperi dimenticati, esigenza questa che sotto l’egida di nuove mode e correnti, si sta facendo prepotentemente sentire oggigiorno.

E questo libro vuole anche essere una sorta di invito a rileggere il giardino tout court nel suo aspetto evocativo, quindi a riscoprire il suo linguaggio allegorico dove si nasconde la complessa grammatica di antichi miti e perdute conoscenze.

Paola Maresca

ANGELO PONTECORBOLI EDITORE

Paola Maresca, architetto è nata a Firenze dove vive e lavora. Entrando nella redazione della rivista Psicon, diretta da Eugenio Battisti sviluppa il suo interesse per il simbolismo nell’architettura. È autrice di numerosi saggi su libri tra i quali: Lo Stanzino del Principe in Palazzo Vecchio (1980), Firenze. La cultura dell’utile(1984), Alla scoperta della Toscana lorenese. Architettura e bonifiche (1984), La fortuna degli Etruschi (1985), Il giardino romantico (1986), Il concerto di statue (1986), Gli Orti di Parnaso (1989) e articoli su riviste specializzate quali Psicon e Arte dei Giardini. Storia e Restauro. Da alcuni anni in funzione del compito istituzionale del proprio Ufficio si occupa di beni culturali partecipando anche a convegni in Italia e all’estero su questo tema. Ha pubblicato “Boschi sacri e giardini incantati”(1997), “Giardini incantati, boschi sacri e architetture magiche” (2004), “Giardini, mode e architetture insolite”(2005), “Giardini, donne e architetture”(2006), “Giardini simbolici e piante magiche”(2007), Simboli e segreti nei giardini di Firenze (2008) e Orti e piante magiche (2009). Dirige inoltre i Quaderni “Giardino e Architettura”.